THE MILLING PROCESS

As a follow up on our last post on Raheen Mill in Clonmel, here Billy explains the milling process which was likely followed at the site in a little more detail.

As a follow up on our last post on Raheen Mill in Clonmel, here Billy explains the milling process which was likely followed at the site in a little more detail.

The eighteenth century Mill at Raheen was typical of it’s time, comprising a vertical waterwheel used to grind grain, principally oats or corn. The original wheels were known as “Scud Mills”, where an open stream or river was utilised. Later mill-races were developed at a higher level along the river to guarantee the water flow. From a survey carried out by Shirley Markley in Clonmel, the undershot waterwheel was the most commonly used. These wheels were the only types which could be installed along the banks of large rivers in areas of low relief.

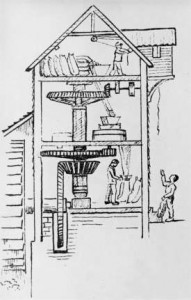

The plate to the left shows a sketch section through a typical mill, featuring a water wheel, wheel pit and wallower on ground floor, grinding stones on first floor and storage area on second floor (source: www.norfolkmills.co.uk ). Typically the internal working parts of the mill were still made of native hardwoods like apple, oak and crab-tree. Oak in particular was used for making mill-shafts because of its durability. In terms of the vertical waterwheel the power terminated with the wheel shaft inside the mill in a large cogged wheel, known as the trundle wheel. The cogs were pegs mortised into the rim of the trundle wheel in the early examples. As it turned, these meshed with the vertical staves of a lantern pinion which turned the central vertical shaft. On the floor above was the pair of millstones, the lower “bedstone ” was fixed in position while the upper “runner stone ” rested on top of the vertical shaft and rotated with it. Towards the end of the eighteenth century, the wooden trundle wheel would have been replaced by a large bevel gear – a solid casting five to six feet in diameter, rotated on the inner end of the wheel shaft. Pulley drives were often taken off the spindles to power the sieves, fans and dusters on the meal floor.

In 18th century mills there were approximately four stages in the milling process. The first stage was “shelling” where through grinding the outer casing and kernel of the grains i.e. seeds and hulls respectively, were separated.

Following this the grains were reground with the stones set closer together. This produced a coarse meal, containing a fair proportion of impurities e.g. whole kernels, passed downwards along a wooden spout on to a meal sieve. There then followed the “sieving” process whereby layers of perforated plates set in a wooden frame, one below the other, sorted the fine meal from the heavier grain. Finally, the meal went to the “sacking” stage via a small chute or spout. Meanwhile, the coarser, unground kernels were screened and either rejected or elevated back up for further grinding.

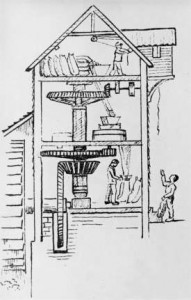

The illustration to the right depicts a profile of typical 18th century mill showing bin floor, stone floor and meal floor(Source – www.angelfire.com/folk/molinologist/problems.html ).

For further information on mills and milling contact Billy on 091 765640….

Some of the principle finds from the excavation at Raheen Mill can be viewed on the blog here and here.

This entry was posted on Tuesday, December 14th, 2010 at 12:05 pm. It is filed under About Archaeology, About Marine and tagged with Archaeological excavation, archaeologists galway, Clonmel Flooding, consultants, galway, mill buildings, mills, raheen mill, Tipperary.

You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed.