Of the people, By the people, For the people

Guest Post from Southie Sham.

Here’s a second guest post from Southie Sham. Southie’s our man in North Dakota in ‘A-Merry-Ka’ and is a Principle Investigator archaeologist. An Irishman, he’ll occasionally post his sometimes skewed thoughts on living in the New World and North American Archaeology. Today SS compares Irish and American approaches to planning and the cultural heritage resource.

Today – Of the people, by the people, for the people.

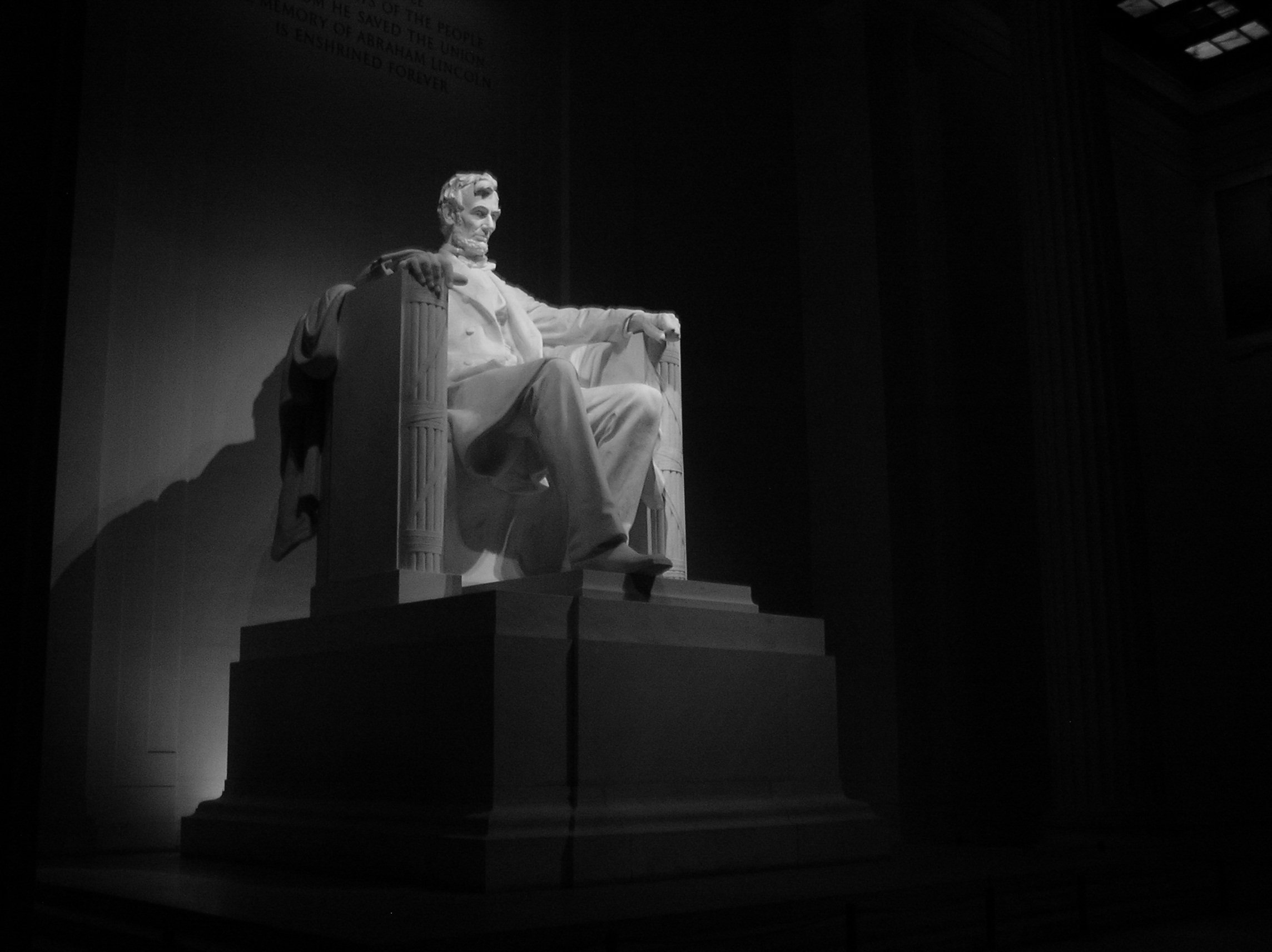

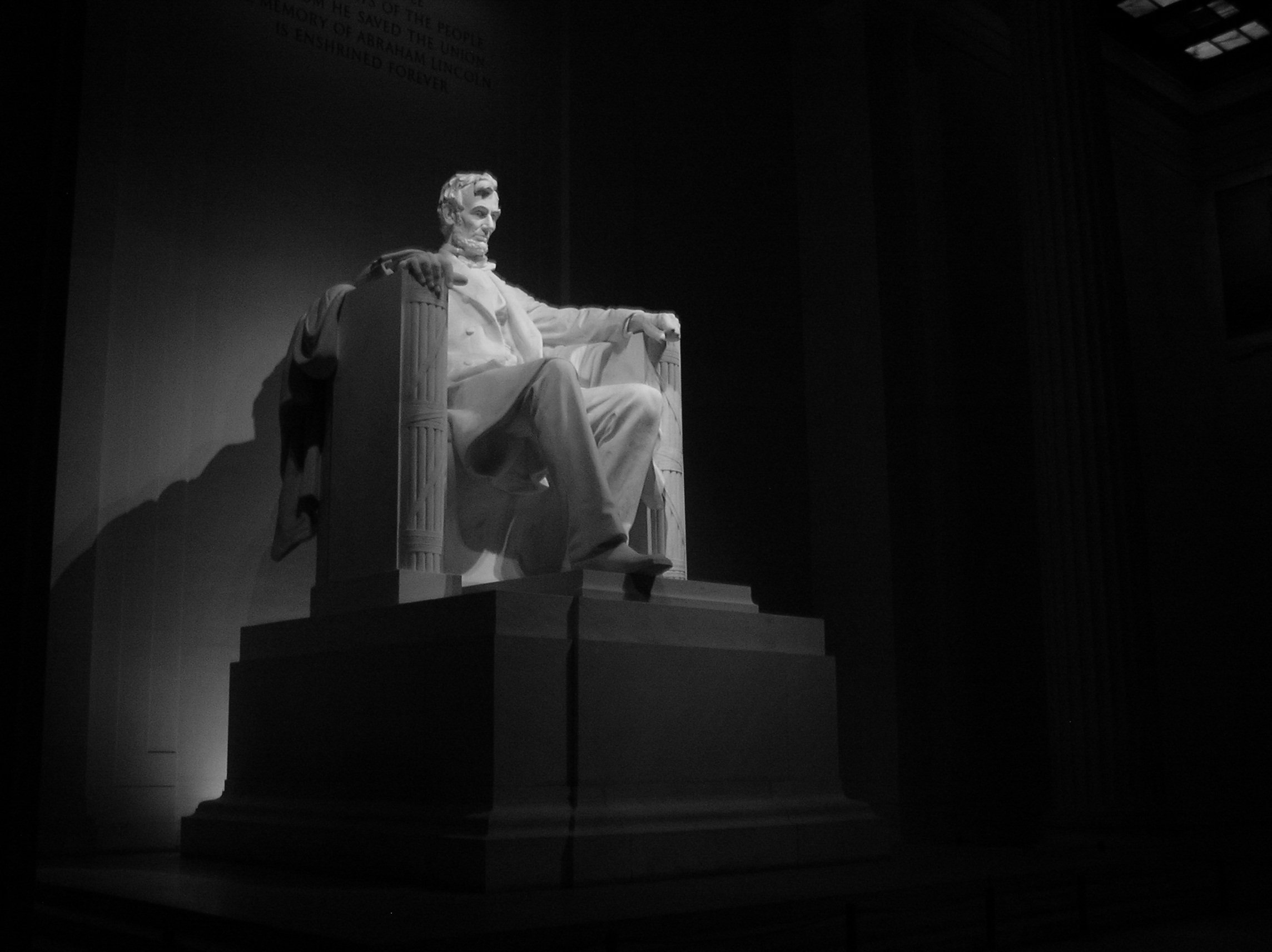

Lincoln, 3am, after 2 bottles of Pinot Grigio (the photographer, not Lincoln)

Last week I finished a two day training course offered by the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation (ACHP) in Washington D.C. ACHP is a federal agency whose job it is to advise the executive on matters relating to all things historical, pre-historical, or just plain old. The course dealt with Section 106 of the National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA) 1966, which deals specifically with federally run or funded, schemes that have the potential to impact on cultural material; and I thought it might be interesting to briefly compare the American process with the Irish planning process for government funded projects.

The planning process for similar schemes in Ireland, is dealt with in the Planning and Development (Strategic Infrastructure) Act, 2006 (PDSI). The first immediate difference concerns who is covered in these pieces of legislation. In the US, NHPA and Section 106 in particular deal specifically with projects run by federal agencies or dependent upon federal money. In other words, projects where the US government is either directly or indirectly involved. In Ireland the PDSI deals with any infrastructural development that is considered of “national importance”, which means it can be paid for by money from the private or public sector, or a combination of both. This obviously leaves the door open for Public Private Partnerships (PPP’s) which the government has used to great effect in various schemes including road building.

Read more under the fold….

The philosophy behind both bills is also markedly different. NHPA was introduced in 1966 as the US was finishing the last of the big highway projects. These new roads had cut vast swathes through previously pristine countryside, as well as utterly destroying many cities historic down-towns. One need only drive through a city like Providence in Rhode Island to see the results. Planners realized, a little late perhaps, that untold damage was done to rural and urban historic and pre-contact (the time before the coming of the white man) archaeology and something needed to be done to ensure the protection of what remained. On the other hand Ireland had in place before the recent building boom, some of the finest cultural resource protection legislation in Europe in the form of the National Monuments Act 1930-94. Too good in fact, and when the road building started in earnest it was found that a lot of this legislation was getting in the way and holding things up. As a result of publicly perceived delays to national infrastructure caused in part, it was alleged, by over-enthusiastic archaeologists, need was seen to “stream-line” the planning process so that infrastructural development could continue with fewer delays. Hence the introduction of the PDSI Act. In essence, NHPA is born out of a desire to preserve and protect cultural material, while PDSI seeks to speed-up and aid development.

Both seek to achieve their goals in very different ways. Section 106 emphasizes the importance of pro-active consultation. A “good faith” effort must be made on the part of the federal agency to consult with any and all interested parties affected by the proposed works. These parties include local residents, Indian tribes, local historical societies etc. Failure to notify these groups of the proposed project, or engage with them in a meaningful way, leaves the whole project susceptible to legal action. And, it should be noted, running an advertisement in a local or national paper is not considered a good faith effort, on the basis that not enough people read public notices in newspapers! This consultation must end with a negotiated settlement agreed to by all parties.

Compare that with the Irish system. A desire to ‘stream line’ immediately implies a reduction in the number of people who have the potential to become involved in a process. Under Irish law the first thing that happened with the passing of this legislation was that local authorities were removed from the immediate planning process. They do have an obligation to provide official comment on any development within their remit, but have no say in the planning or decision making process itself. Secondly, the developer must make an attempt to notify the public of any proposed undertaking, but unlike in the US this notification may take the form of a simple newspaper ad, and it need only run for six weeks! During the six week “consultation phase” the plans must be available in the offices of the local authority, but no further steps need be taken to facilitate public access to, or discourse on, the subject. Once those six weeks are up, no objection, regardless of its veracity, can be lodged.

As happened to the objectors to the Tara motorway, who lodged a formal objection based on well documented archaeological information, but because it was submitted after the initial 6 week public consultation phase, the courts were obliged to find it inadmissible. The protestors argued that six weeks did not allow enough time to adequately prepare their objections and compared it to the apparently open-ended time table offered to the developer. However, the courts again were obliged to point out that the government had the prerogative to write legislation and that if the government, or its agents, had determined that six weeks was sufficient time the courts could not second guess them.

By removing locally elected counselors, in addition to placing a severe limit on the time available to the public to educate and form an opinion on a given project, all in the name of “fast tracking” a project, the Irish system leaves itself open to accusations of being pro-developer and not duly interested in discussing the concerns of the public. On the other hand the American system is clearly and deliberately rooted in the concept of public discourse and inclusion. Lincoln’s government “of the people, by the people, for the people” has not, it seems, perished from the earth. Only from some aspects of Irish law.

This entry was posted on Saturday, February 21st, 2009 at 12:33 pm. It is filed under About Archaeology and tagged with ACHP, CRM, Cultural Heritage Legislation, planning, Roads, Southie Sham, Strategic Infrastructure Act, Tara, USA.

You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed.

You forgot to mention your visit with the Obamas while in D.C. Given that you so recently declared war on the US, I have taken it upon myself to notify Homeland Security. Expect a visit soon!

… on a more serious note. I find it surprising that the American system is more open to public input. Not because of anything to do with governing concepts, but rather due to an emphasis on development in this country. We will destroy entire mountain tops to extract a little coal or oil, and we will fill in wetlands to put in condominiums (that sometimes sink later and I feel a little schadenfreude at that).

jenH – As far as blowing up mountains, there was an element who thought that the gold under a certain Croagh Patrick might out-weigh the cultural/religious importance of said mountain. Only for the HUGE public outcry that would have followed any such permission, I’m not sure our own government/political parties would have been too quick to halt mineral exploration. Building houses in wetland? If you saw some of the ribbon and one-off building permits that were granted in Ireland over the last 10 years, then you wouldn’t feel so surprised.

And please, I have no idea who Schadenfreude is but we would all appreciate if you kept your personal life to yourself.

No comment on the archaeology. I’m sure it’s all good. But I’m going to call you on a grammatical point: your use of the apostrophe in the possessive form. Please start by changing your title. It should read “The Moore Group Blog”, or “Moore Group’s Blog”. As for the idiot above, I give up. I just give up. The English were good enough to give you their language, the least you could do is to use it correctly. Show some respect.

Thanks KMP – the omission of the apostrophe is a style thing. Sometimes we use it, sometimes we don’t. And, given that the English language was imposed upon us, we feel we can use it any way we want (Dec).