Tayleur Wreck

Posted by Eoghan

Published previously on Moore Marines blog and originally published in the Bulletin of the Australasian Institute for Maritime Archaeology in 2004, we’ve posted below Eoghan’s paper by way of commemorating 154 years since the sinking of the Tayleur in January 1854.

Tayleur, a victim of technological innovation

On 21 January 1854, the British-built Iron Clipper, Tayleur was wrecked on Lambay Island, 21 km north-west of Dublin Bay. This much lauded vessel was on her maiden voyage to Melbourne, with a miscellaneous cargo and over 600 passengers and crew. The sinking of this revolutionary new ship during a time of great industrial advancement shocked many people and highlighted how a failure by contemporary mariners and designers to understand the effects of recent technology in vessel form, construction and material could be so costly.

View from Lambay of Wreck Site

Background

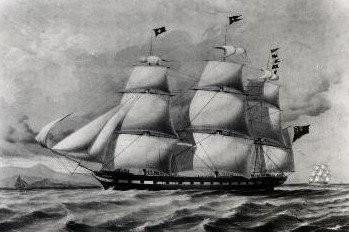

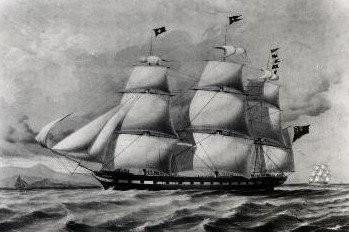

Tayleur was the largest of eleven iron ships built by the Bank Quay Foundry during a short-lived programme of shipbuilding lasting from 1852 to 1855 (MacGregor, 1973). Prior to the commencement of this programme the company was more noted for its proficiency in heavy castings and iron working. The ship was designed by the renowned clipper designer William Rennie of Rennie and Johnston, Liverpool, who had just begun to develop an interest in iron shipbuilding (Starkey, 1999). The ship was originally designed as a screw steamer but whilst on the blocks its form was changed to that of a clipper owing to the lack of availability of a suitable engine. One consequence of this modification of the ship form was an increase in the ship’s dimensions; they increased from 204 ft x 36 ft x 23 ft (62.22 m x 10.98 m x 7m) to 225 ft x 39.4 ft x 27.6 ft (68.62 m x 12 m x 8.4 m) (MacGregor,1973). The ship was built at breakneck speed and on 5 October 1853 it was launched, just six months after its keel was laid (Warrington Guardian, 9 October 1853). Tayleur was then towed down the Mersey River to Liverpool where it was fitted out for its journey. This was also undertaken with considerable speed and on 14 January 1854 the ship was taken to anchorage in the Mersey Channel to await passengers and crew.

Tayleur sailing

On the recommendation of Captain Townson, the Examiner of Masters and Mates for the Port of Liverpool, 29-year-old Captain James Noble was specifically chosen by the owners of Tayleur, Moore and Company for the task of commanding their new ship (Starkey, 1999). Prior to this, Noble had a distinguished career with the trade clipper Australia making a number of swift passages to Australia. However, from the outset Noble appeared to have been at odds with his new command. During the early stages of the ship’s construction he accidentally fell into the main hold and was nearly killed.

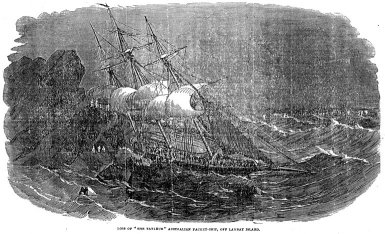

On Thursday, 18 January Tayleur was taken in tow by the steam tug Victory to be led into the Irish Sea from where they would begin their voyage. All went well during this journey except that the Liverpool Port pilot noticed one point of difference between the ship’s three compasses. It was not until the tow was cast off that the true nature of the ship became apparent. Not only were the ship’s compasses erroneous but the vessel handled very badly. Captain Noble was later to recount how it took up to one hour to change tack and the ship would loose up to five miles (8 km); normally a ship should take fifteen minutes to change tack and loose one mile (1.6 km). The reason for this is several fold and will be discussed later in this paper. As the voyage progressed the ship encountered bad weather and dense cloud cover negated the possibility of obtaining astral observations. On the morning of Sunday, 21st, land was sighted. It was attempted to wear the ship from this danger but difficulties in manoeuvrability made this impossible. The two forward anchors were dropped but they almost immediately snapped their cables and the ship slammed into the Nose of Lambay Island where it sank within twenty minutes of the impact with the loss of over 400 people.

Compass

The Board of Trade enquiry into the loss of the vessel concluded that compass error was partially to blame for the sinking. Compass deviation caused by the proximity of the compass to ferrous material was a well-known phenomenon in the 1850s. As far back as the 16th century, the effect of iron on the ship’s compass was recorded by the famous Portuguese navigator João de Castro. We also know from records that both Captain Bligh and Cook were aware of this phenomenon, so too was Matthew Flinders during his 1801-02 voyage around Australia (Williams, 1994). Even as recently as 1835, Commander E.J. Johnston conducted experiments into this phenomenon with his warped paddle steamer Garryowen (Williams, 1994; MacCarthy, 1985).

The three main compasses on board Tayleur were fitted by John Grey ‘compass maker to Her Majesty’. He fitted and compensated the ship’s three compasses two months before the sailing of the vessel, and prior to the loading of the ship’s cargo (Starkey, 1999). The Coroner’s inquest into the sinking of the ship records that whilst the ship was being steered out of the Mersey estuary into the Irish Sea, the pilot noticed a point of difference between the compasses. Later in the journey, further discursion of up to 1½ points were recorded (Melbourne Argus, 27 April 1854).

As already explained, the phenomenon of deviation was well understood by mariners and several experiments had been undertaken to investigate its cause. What was not known at the time was that regardless of how much research was conducted into this topic, it would not have been solved.

The reason being was a lack of a theory of magnetism. This theory later concluded that ships have two kinds of magnetism; induced and permanent. In iron ships, the induced magnetism is brought about naturally by the effect of the earth’s magnetic field on the soft iron of the ship. This form of magnetism is altered as the ship alters course or moves to an area of differing magnetic content. The second form, permanent magnetism, is induced by the vibration of hammering and riveting on the ship’s metal. It aligns the molecules permanently in a way that is determined by the lie of the ship during the construction (Williams, 1994). In the absence of such a theory, the problem of deviation of the ship’s compass could not be approached analytically or fully understood.

Rigging

Although the Board of Trade and Coroner’s enquiries make little mention of the rigging affecting the efficiency of the ship, there are indications as to how it affected the handling of Tayleur. Passenger testimony would appear to indicate that the contribution it played was quite significant. Robert Davison, a steerage passenger and seaman of 26 years is recorded as being surprised when he found riggers still completing their work the day before the ship was due to sail. He also noted that the natural fibre running rigging ropes had not been properly stretched.

Before natural fibre ropes are fitted as part of rigging, they first need to be stretched. In doing so the rope becomes less elastic as the strands bind together and combine to produce a rope of greater breaking strain. In addition to this, the number of frayed rope filaments, which often affect the smooth running of the rope through pulley blocks, are reduced.

By neglecting to properly stretch the newly applied running rigging ropes, the riggers severely affected the handling of the ship. Not only were the ropes difficult to handle, and snagging in the pulley blocks, but also they were quite elastic which made setting of the ship’s sails very difficult. In the Coroners’ Enquiry, Captain Noble stated that he stood for fourteen hours on the same tack despite the fact that there was a ‘heavy wind’ blowing (Melbourne Argus, 27 April 1854). The fact that the master of the ship stood on the same tack for so long coupled with passenger reports of the crew having difficulty in reefing the sails (three hours to reef a topsail) appeared to indicate that there were problems with the new running rigging and this was adversely affecting the ship handling.

Sails

Although there are no available sail plans for Tayleur, there are several detailed illustrations. One of the most prominent is The Illustrated London Times of 16 November 1853. During the Board of Trade enquiry into the sinking of the ship, Captain Noble commented that he considered the positioning of the masts as being too far aft and this contributed towards the difficulty in handling the ship. Examination of contemporary illustrations of the ship would appear to concur with this assertion. It is clear from the illustrations that both the mainmast and mizzen mast were too far aft, and the foremast was placed too far forward. As a consequence, the ship’s fulcrum, the centre of lateral resistance was moved aft to a centre of effort. The net result of this shift was increased difficulty in handling and poor response (Steel, 1978). Considering the original hull form, its innovative design and information contained in contemporary illustrations, it appears that the ship’s main hold was positioned in such a manner that it necessitated placement of the mainmast and mizzen mast further aft at the expense of the balance of the ship. One of the most obvious explanations for this was that the ship was originally designed as a steamer and later changed to a clipper. During this change the designers appeared to have retained some steamer components such as the large hold, allowing for the possible refit of the vessel with a steam engine at a later date.

Rudder

Contemporary newspaper accounts record Tayleur as having a patented ‘semi-automatic’ rudder. In the Coroner’s Enquiry into the sinking of the ship, Captain Noble is recorded as saying he believed the ship’s rudder to have been too small and as such was partly to blame for the vessel’s poor handling. Unfortunately, the terse reference in the Warrington Guardian is the only reference we have to the ship’s rudder. Investigations in the British Patents Office failed to yield any records for any such patented device in the two years before and after the Tayleur’s construction.

Considering Captain Noble’s assertion that he thought the rudder too small, and in light of the above mentioned significant changes made to the ship in the early stages of the construction, it is quite possible that this was indeed the case. As part of the change from a steamer to a clipper hull the ships dimensions were increased. It appears likely that during the course of this transition the designers and builders had sufficient belief in their new ‘semi-automatic’ rudder that it remained unadjusted. Its size was obviously too small for that of the enlarged clipper and consequently it restricted the vessel’s manoeuvrability.

Sea trials

The final and probably one of the most significant oversights of contemporary merchant mariners at the time was the absence of sea trials. Whilst sea trials or a shake down run was always completed by the navy prior to the commissioning of a ship, in the merchant navy time restraints, economics and low crew numbers did not always permit such activities (Bourke, 2003). In the case of Tayleur, the ship was readied at incredible speed (two months after its launch) then sat in the Mersey Channel for only one week awaiting the arrival of crew and passengers. Given the speed at which it was readied for sea it appears that even if sea trials were a common occurrence Captain Noble and his crew would not have had time to do so.

This was a very unfortunate case. Captain Noble had already been at odds with his new command and had he been able to sail the ship for even the shortest time he would undoubtedly have been made aware of its defective handling and possibly been able to rectify some of the more obvious flaws.

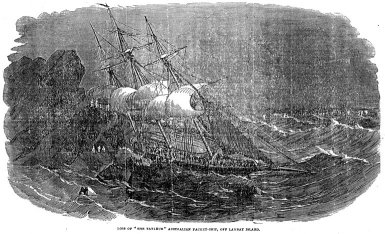

Tayleur Sinking

Conclusion

The sinking of Tayleur and the loss of over 400 lives was a very unfortunate event. To many at the time it cast a shadow of doubt over the suitability of iron as a material in the construction of ships. To others it further highlighted the need to properly assess the influence of iron on ships’ compasses. Some people accused Captain Noble of neglect whilst others blamed the foreign crew claiming they could not understand the Captain. Both were later proven to be untrue. Most significantly, it appear that the failure of all parties involved to conduct sea trials prior to the commencement of the journey was the gravest error. Had such trials been conducted they would almost immediately have become aware of the inherent flaws of the ship, its masts placed too far aft, the improper state of the running and standing rigging, the unsuitability of the rudder and the compass errors.

References

Bourke, E.J., 2003, Bound for Australia. Power Print, Dublin.

McCarthy, M. (ed.), n.d. [1988], Iron ships and steam shipwrecks. Papers from the First Australian Seminar on the Management of Iron Vessels and Steam Shipwrecks. Western Australian Museum, Perth.

MacGregor, D.R., 1973, Fast sailing ships, their design and construction 1775-1875. Nautical Publishing, Hampshire.

Starkey, H.F., 1999, Iron clipper ‘’Tayleur’ the White Star Lines first Titanic. Avid Publications, Merseyside.

Steele, D., 1978, The elements and practice of rigging and seamanship. Two Volumes. Sim Comforts Associates, London.

Williams, J.E.D., 1994, From sails to satellites. Oxford University Press, New Hampshire.

This entry was posted on Wednesday, April 16th, 2008 at 1:33 pm. It is filed under About Marine, Papers & Reports and tagged with dublin, environmental consultants galway, Lambay Island, Marine archaeology, marine environment, Tayleur, Wrecks.

You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed.